- Home

- Raymond Hutson

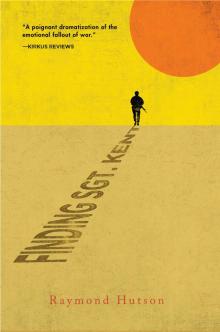

Finding Sgt. Kent Page 7

Finding Sgt. Kent Read online

Page 7

“Bullet,” I whispered. “Matching one on the back.” Garcia wanted to stick a dart in my chest, worried my lung was going to collapse. “Went in just above the lung.” I still remember Garcia pressing gauze into my chest, fist like a drill.

Her fingers crept over my trapezius and paused at the dimple there. I let my hand fall to her hip, my fingers over her buttocks.

“I’m a little foggy,” I said. “I take medicine at night. Supposed to keep the nightmares away, but I black out with it too.” It was a lie—I hadn’t taken it for a week.

“You don’t remember me coming here?”

“Was I pushy?”

“Maybe I was pushy. But you can be wild.” She drew her finger down the center of my chest. “Scary as hell.”

“Did I scare you?”

“You scared the piss out of those guys.”

“Guys.”

“Jesus. You really don’t remember, do you?” She pushed the pillow against the wall and sat against it, her breasts free momentarily before she drew the sheet up, tucking it along her legs. “There were these guys, really just one guy, and I know, I know, my mistake, I fucked up.” She fluttered her hands. “Just one guy. After work. He said, ‘Why don’t we go smoke a joint?’ And it had been a bad shift.”

“Shift. Where?”

“Bad Daddies. Restaurant. Really, it’s just a bar. On Sprague. So we sit in his car and smoke the joint, and listen to his CD, some kind of devil-screaming shit, and he starts coming on, and I told him his music was giving me a headache.” She paused. “I think I told him that, anyway. And I got out. Got in my own car.”

She jumped out of bed and ran to the patio door, then strolled back to me.

“Just wanted to make sure it was still out there.” She slipped under the covers and it was warm again. “When I got here, he’s right behind me, and he’s got another dude in the car with him, and they both got out and started to push me.” She looked at me like I might know the answer. “And I’m asking myself, where’d he come from?”

“And I came out.”

“You did.”

“You’re jerking my chain.”

“You came out on the balcony. With a flashlight.” She glanced at the kitchen table. “That one probably.”

A tactical light, meant for a rifle. Bright as an arc welder. “I scared them with a flashlight?”

“You yelled, ‘I’ll blow your fucking heads off!’ and I don’t think they could see you. Stoned and everything.”

“I’m really flattered. That you’re here, I mean.” I buried my face in my hands, tried to put a memory together. “And they just drove off, just like that?”

“Yeah. No, you said something else first. Like Indian or something. Wassee Wah-wah?”

I straightened up, opened my eyes. “Tass leem shah. Wasss-lah wahchah-wah.”

“That.” She pointed at me. “That scared the shit out of them. Like it was a curse or something.”

The vaguest images came to mind, like the fading outline you see after staring at a bright object too long, and things could have gone very differently.

“It’s from the Army. Pashtu. Means, ‘Surrender, drop your weapons.’” I mustered a smile. “Had to memorize phrases. Just said it out of habit, I guess.”

Her eyes narrowed, trying to measure my mood. “And I just came up, knocked to, like, thank you. You didn’t have your shirt on, and it felt so good when you put your arms around me. It was all Mother Nature after that.” She nodded against my head and gave me a kiss. “You really had to learn stuff like that? Bet you had to kill a whole bunch of people in the Army, didn’t you?”

“A few.”

“I don’t know if I like that.” Her voice trailed off, like she was starting to fall asleep again.

“Part of the job. Did I say anything else?”

“Not much. You were like a man possessed. Like you were gentle and everything, but we just had one thing on our minds.” She tweaked my nose and kissed me again.

“We fucked.”

“For about two hours. I don’t think you fell asleep until about five, and then you snored. Really loud.”

“Sorry.”

“You didn’t say much, but every once in a while you’d hold me still, like really hard, hush me with your fingers over my mouth, like you’d heard something. Then we’d go at it again.”

I might have been hallucinating. Dreams get all tangled up with daylight and reality, and I thought it was getting better. I buried my nails in the pillow until they hurt. If I’d mistaken her for a threat I could have broken her neck.

“Can I see your gun?” She stood slowly and wandered naked, dazed, back to the table and, realizing the curtains were open, drew them.

“Don’t have one.”

“Not even a pistol? You mean you just—”

“Just a flashlight. I could have chased ’em with the machete if you liked.” We laughed. “Jesus. Don’t smoke pot with people you don’t know. Didn’t anybody ever—I mean, shit happens. Look at us.”

“I don’t believe in guns, anyway. And I’m not complaining.” She picked up her blouse and started to pull it on, staggered, and caught herself, still naked from the waist down. “I’ve had my tubes tied, if you’re worried about that.”

When I was a child I used to think that if I didn’t look at someone I’d be invisible. I pulled on my BDUs and a T-shirt like that, not looking her in the eye, embarrassed, frustrated by a loss of control apparently only I was concerned about. When I stole another glance at her she was dressed, wandering around my apartment like a stray cat, eventually bending over by my bookcase.

“Sure read a lot for an Army guy.” She did a little double take. “You have a book of Man Ray.” She glanced back at me. “He was one of my favorites.” She pulled it out with her fingertip, leafed through a few pages in disbelief, then put it back in place. She stepped sideways, drawing her fingers over the rest of the case, mostly military field manuals, a couple of paperbacks by Bernard Lewis, Thomas Friedman. “You into surrealism?”

“No. Just liked the cover, I guess.” I found the book at a Goodwill.

“I was an art major a couple of years,” she exhaled wistfully. “At Eastern.”

“Didn’t finish?”

“Shit happens. Like you said.”

She had washed off her makeup, and I was surprised how much younger she looked. She wasn’t even thirty yet.

I walked her back to her door and stepped in for a minute after she unlocked it, leaving the door open. She seemed satisfied nobody had gotten in.

“Where are the kids?”

“At their dad’s. Brenna and Casey.”

Brenna and Casey, Brenna and Casey. Brenna and Casey. I tried to remember.

“They’ll be back tonight.” She looked in the empty fridge, back turned to me. “Can I make you any breakfast?”

“I’ve got a couple of things to get done today. I’m already late.” I don’t think she really wanted me to stay right then anyway.

When I got back to my apartment I showered hot, left the fan off so it would get thick with steam. I keep my hair short; only way I know it’s clean. Never felt really clean in Afghanistan. Six years and always some layer of grit or oil or some little skin-eating mites burrowing in; sometimes you even had to put the same shit-stinking uniform back on.

I shampooed twice, dragging my nails across my scalp. The wash cloth had two long, irregular blue-black smudges. Jennifer’s eye makeup. I pressed it deep into my face, around my neck, across my lips. I thought of Alexandra.

–––

When I left the Army the first time in 1993, I joined the reserves, went to school a couple of years in Missoula, got an associate’s in business, and married Julia, a cousin of a guy I’d known in Iraq. I couldn’t find full-time work right away, did simple taxes during tax season, and ended up living in her parents’ basement. I helped out on their ranch and could do anything they needed, but at some point the details of my mom came up

—being candid seemed the most honest path—and they got the notion I was some kind of trailer trash. Everything I contributed after that met was with a little smirk and a nudge. I tried to give them advice here and there on how to avoid a tax or make good on an investment and her old man would grin and let me know he had a buddy that took care of the big money, thank you. Let me know they weren’t looking for grandchildren too soon. I even stacked twelve tons of hay bales for them one afternoon, and they complained I left too much air and took too long. They were complacent when Julia started screwing around with the son of a rancher, and I knew then it was time for me to go. And she’d been the crazy jealous one.

Needing a purpose and still in the reserves, I requested active duty and they sent me to Kosovo in early ’96, attached for a while to a UN battalion where our job was, apparently, to prevent genocide, if we happened to run across any. We started thinking of ourselves as meals-on-wheels. We went everywhere with our guns unloaded.

We were using spotlights, moving refugees into a camp north of Sarajevo one night, mostly Muslim women, when it became obvious that snipers were using the illumination to gun them down. Nobody turned the fucking lights off; it was like hunting at a feed lot. The absurdity amplified tenfold while we supervised the exhumation of a mass grave near Srebrenica. Buried for about six months, mostly boys, it seemed. Dark flesh that sloughed off the narrow pelvic bones, little bitty delicate femurs and forearms tumbling from the sleeves of blue uniforms, gold patch on the breast pocket. School blazers. Sometimes a bullet hole through the little patch, used as a target. The stench nauseated us all; not because we had not seen death—we had marched in its aftermath for two months—but because simple immersion in that odor, at that concentration, does something primal to your appetite. Obviously a bunch of kids went off to their private school one day the previous fall and never came home. UN marked it as a military gravesite. I fucking boiled when I understood that, asked myself what my dad would have done, like he was Jesus. Couldn’t sleep, felt so phony being in uniform in front of those people, and I began to understand their indifference.

Eventually I pressured my CO to let me tag along with a Marine Corps unit actually possessing live ammunition, thinking that somebody needed to be killed for what I’d seen, and if anybody was going to kill anybody, they would be the ones to do it. After a couple of days of eating their food I explained my logic to one of their lieutenants and they choppered me back to a US Army unit that promptly flew me back to Landstuhl for a medical exam and a thirty-day medical leave. They farmed me out to a German psychiatric clinic that put me in some kind of group recreation class. I checked in and worked on jigsaw puzzles for one afternoon, and never went back. Caught a Eurorail back to Kosovo. Volunteered at a Red Cross station for the rest of that time, evenings spent drinking too much rakia, belching the sweet plum stink of it through the night.

One morning I awoke with Alexandra on my arm, sleeping in her grimy, cold eight-by-ten room, hot plate on a crate, sink in the hall, a toilet one floor below. She understood some English but couldn’t read or write it, and she couldn’t, or wouldn’t, speak. She’d do everything to keep me from leaving at night—tug at my clothes, hang on my neck with both arms, cry. But then the sex would turn bland and passive. She clearly didn’t want to be alone. She was older than me, or had aged faster, her angular, sculpted Slavic face furrowed in perpetual alarm, wide eyes, cigarette burns on her breasts, deep scars on her buttocks from the inside of her thigh to her groin. I think she had been raped with a spiked object at one time. There was a numbness about her I couldn’t awaken.

In a satchel near her bed she kept a dog-eared picture of a bright-eyed boy, twelve or fourteen. She never showed it to me, but I found it the first morning I was there while she was downstairs. I got the notion it was her son. We walked the streets in the mornings and I would buy some food, and she seemed happy, sometimes radiant. We kept a mental roster of which cars were new, parked along our route to the square. When there was one you didn’t recognize, it might blow up later, so you’d scurry by on the far side of the street. People at home have no idea what a blast like that is like. You don’t really see it happen; it doesn’t progress through stages. One minute the world is bright and normal and the next second you’re hit with this wall of pressure, like a thousand nails through your body, like every bone is broken and your eardrums burst. Then dust so thick you can’t see your fingers, and people who are still alive knock you down or step on you because they can’t see either, and nobody can breathe. After a couple of minutes light comes down from the sky and, as the dust blows on, you see the ground and pieces of people—heads, arms, chunks of torso. They don’t bleed very much because so much dust has been driven into them, through them. That happened to us once; the car was easily a block away, parked too far from the curb, like someone had just stopped in the street and walked away. I was on top of Alexandra when it cleared. I don’t think she could hear me again until that night.

All of that time, three weeks or so, I convinced myself that I could actually do her some good; I stopped drinking and gave her money, food, blankets. In the end I went back to Tuzla, and when we marched through Vogosca two months later, the building we’d slept in had been demolished. I never learned if she was Croatian or Serbian.

I hadn’t thought about her in ten years, but waking up with Jennifer dug it all up again, how useless I’d turned out to be when someone was counting on me. I only intervened last night because I was sleepwalking, flashing back to Nangarhar or some other shithole. I wiped the steam off the mirror and smiled, but I couldn’t look sincere. The face in the mirror was ugly, damaged, not one I knew. It had seen stuff I didn’t want to remember.

I threw a few changes of clothes in my backpack and got dressed, trying to look as civilian as possible. Gerber. Sunglasses. Flashlight. Might have to scare bad guys again. I flattened the letters and put them in chronologic order, leaving the last few unread in their envelopes. Medication. I took one pill out, rolled it in my palm. Puts you in condition white—not a good way to be on the highway. I dropped it back in the bottle and shoved it in a side pocket. By the time I reached I-90, I’d decided on the Yakima Valley and headed west.

I had a couple thousand bucks in my pocket to throw at this little adventure, more if I wanted to use credit cards. I get just shy of $3,600 a month in disability, tax free, with a nice lump sum three months ago. Plus about $1,500 retirement. At times it doesn’t seem like a bad trade for a few nightmares and a limp. Lots of people have bad dreams and don’t get paid a cent. And I could do other things and no one would keep track. Work off the books, so to speak.

I picked up a laptop at Wal-Mart on the way out of town. Sixteen-inch screen was the smallest I could find. Rest of them looked like televisions, all sorts of features for playing games, mostly war games—exaggerated perspectives of tanks, soldiers muscled like superheroes just about crawling off the boxes, sleeves rolled up, wearing some senseless mish-mash of uniforms. Two pasty kids about nineteen stood in line ahead of me debating which edition of Tour of Duty they wanted. I wanted to take them by their flabby biceps and introduce them to the recruiter I’d known eighteen years ago. Maybe introduce them to Marsden’s.

–––

A headwind came out of the southwest, fighting the Corolla all the way. An ANA soldier explained one time how Allah controls the weather, the sun, the wind. Allah sent Katrina to punish the sinful Americans living in New Orleans—everyone in Afghanistan understood that.

“Then why are you guys fighting on the same side with us?” I asked.

“Because you are repentant,” he said. “The evil people were killed.”

The reflectors on the side of the road bent toward me in the sun, the little 1.8 liter Toyota engine whining. Did God, Allah, want me to go the other way, or just fuck with my gas mileage?

I set the cruise control and scanned through the radio. So much attitude and none of it authentic. Maybe they should make music for people like me.

Indifferent music. All the stations sounded the same, except country, but I haven’t had patience for that kind of self-pity since I first heard it on Mom’s table radio. Or the gooey sentimental shit with Mom and Dad and Grandpa and everybody around the fireside eating pie and grinning and playing with the baby. Nobody I ever met had a life like that.

I turned the radio off. They just keep inventing bands and idols to sell more of the same stuff, reinventing ways to capitalize on the same old juvenile angst. I never had an MP3 player like a lot of the younger guys. I liked some classical but didn’t know enough about it to know what to buy. Same with jazz. In Jalalabad I’d listen to local music at night on a small Grundig with a single earpiece I bought at a PX in Germany. Monotonous, hypnotic, lyrics unintelligible, no hint of the emotion, beyond some sorrow; it was soothing and I could fall asleep to it. BBC could be heard any night, always a gentle anti-American spin. Kabul Rock was an odd mix of hip hop, Eighties, badly re-done rock and roll, sometimes in French, other times in Pashtu. The Taliban would blow up their stations every month or so, kill the engineer and the deejay, but a few weeks later they’d be back on the air. A different announcer, some guy probably nineteen or twenty thinking, They won’t get me; that inexhaustible notion of immortality that lets everybody get up every day.

When I wasn’t listening to the radio I was reading. I started with the commandant’s reading list because it was implied that one could advance rank a little quicker. Then I read the same list the Marines posted, then any book I could find that had any kind of award on the cover, thinking it helped my vocabulary. After you make E-5, it dawns on you one day that you’re eight or ten years older than the new guys and, if you answer them with the same kind of trash they speak, they’re not confident you know anything more than they do. Discipline crumbles and somebody gets their ass shot.

I passed the exits to Ritzville. We played them once, or I should say my foster brother did, and I went along for the ride with the rest of the Dunham family, sitting next to Kaye in the back seat. There were half a dozen other little towns out across the wheat fields I wouldn’t know how to get to now, wouldn’t recognize if I did.

Finding Sgt. Kent

Finding Sgt. Kent