- Home

- Raymond Hutson

Finding Sgt. Kent Page 2

Finding Sgt. Kent Read online

Page 2

I stopped at the nurse’s station. A piñata hung from a paperclip over the desk. Teresa sat texting. “What’s the word for today?” I wanted a hydrocodone.

She looked at me and scrolled through the little screen. Screwed up her face. “Punctilious. Know what it means?” Smug girl.

“Means picky. Like, no point in being punctilious about the food here.”

She squinted, lips moving as she read to herself. “You are so right.” The only nurse there who didn’t treat me like I was crazy.

“Means I win a pain pill. What’s with the piñata?”

“Gina’s birthday.” She nodded at one of the aides sitting in the hall checking blood pressure. “We’re gonna let her break it at break time.”

“Is that a pun?”

We entered a village schoolhouse, my first tour in Afghanistan. They had hung a woman of about fifty, a European, from the ceiling fan days before. She was puffy, blue, foul, glasses awkwardly on her face like someone had added them later. It’s always bothered me ever since, when people’s glasses are crooked. Shit had run down her leg beneath her dress and dried there. Some guys started to slide a table beneath her when Lieutenant Johnson gestured us to halt, said something didn’t look right, told us to clear the building. From outside he shot the corpse a couple of times with his M4. It exploded on the third, showering the room with rotting flesh, ball bearings and screws, some buried in the wall. No candy.

“Mr. Kent?” She scanned my bracelet barcode. Tablet in a paper cup. “It’s not candy.”

“Huh?”

“You said, ‘No candy.’”

–––

Zilker was sitting with his yellow pad when I arrived the next morning. He motioned at the chairs, the sofa. “Pick a spot. Anywhere that feels right.”

I chose the sofa but sat at one end, avoiding the stain. The medication rolled over me like surf, but still I felt edgy.

“You told me yesterday your mom died when you were fifteen.”

A lot of things had happened when I was fifteen. I’d been born at fifteen. I bit my lip.

“Drank herself to death.”

I’d never actually spoken those words out loud and sat momentarily soaking up the sound of my own voice. I pondered that day, until Zilker cleared his throat.

“No fucking reason. I used to think when I was small that it was my fault. Later I thought she missed my father.”

He was taking notes with one hand, not looking at the page, perhaps sensing some anger in my posture. “Why don’t you tell me about your house first? Go there now, room to room.” I went on talking about Mom, though—the first time anybody had ever asked.

“It was probably one of the better things that could have happened,” I said. “She was pretty worthless. Take something out of the cart at Safeway, something I needed for school, grab a half-rack of Rainier instead. Slip one in a koozie as we drove back to our mobile in Addy, so often it became some kind of family ceremony.” She felt entitled to that reward. Life was a lottery of magical events. You had to seize an advantage, hang on, hang on, learn to work the magic.

“Robert?”

Zilker stood, tapping my shoulder with his notebook.

“Yeah?”

“You fell asleep. Xanax does that.” He stooped slightly to capture my gaze. “Go on. What did she tell you about your father?”

“Not much. There were three pictures over our breakfast counter. Saint Somebody playing the organ, cherubs looking down at her through clouds. Richard Nixon in a wide mat, letter to my grandparents right next to it saying how the nation was grateful for Dad’s sacrifice, and a chest-up picture of my father in his class A, looking serious, KENT on his pocket tag, looking off somewhere over the photographer’s shoulder.”

“It was a style at the time,” Zilker said. “My wife has a picture of me like that somewhere.”

“I don’t think my dad would have done that. I liked to imagine he’d look anyone right in the eye. Anyway, Mom would say, ‘You’re my little soldier now, Bobby.’”

I rambled on about how he made sergeant before he disappeared, my childhood rife with imagined heroism: Dad leading a platoon out of an ambush; Dad standing in the door of a Huey firing the door gun; Dad throwing himself on a grenade to save his men. He always recovered from this, through some malfunction of the grenade, or his own physical superiority. My dad single-handedly winning a war that, eventually, we lost. I looked up and Zilker had set his pen down, staring right through me.

“Doc?”

He seemed to shudder, then, present again, picked up his pen, rubbed his eyes.

“You were there.”

“Right out of med school. Base hospital near Saigon.” Zilker shook off the memory. “When your mother died—tell me about that day.”

“The last six months she got sick almost every Sunday, puking in the toilet with the door closed. I’d lie in bed, open the windows a little, listen to cars on 395. Not even my Walkman would drown her out. One morning I went in to pee after she was done. Splatters of blood all around the rim where it hadn’t flushed away. She’d be sick the rest of the day, stumbling around, taking Tylenol, drinking more beer. Eyes would get yellow, then she’d be better for a few weeks.”

“Her liver?”

“Yeah. It was autumn, a week before Halloween. I was sitting in English Comp when they called me into the office, said she’d been taken to the hospital. A neighbor had come over when she noticed the car was still there, could see her lying on the floor.” I can’t remember the rest of the day. “When I finally got home that night, she’d bled all over, some half-assed job of mopping it up, chairs pushed back, furniture shoved out of the way by paramedics. Neighbor drove me up to Mount Carmel to see her. She was all puffy, like her bones had dissolved, just lyin’ there, eyes amber, belly big, thin and tight like a water balloon, breathing fast and shallow, stink of shit in the air. I asked the nurse why she was so yellow.”

I glanced at Zilker, listening so intently, but he looked over my shoulder at someone gesturing through the window in the hall. An aide opened the door, put two bottles of Aquafina on the table.

Zilker pushed a bottle over to me. “Keep going. Your mom was jaundiced.”

“Mom woke up, opened her eyes and grinned, said, ‘Cause I’m the Great Pumpkin, sweetie.’ She had dark blood around her teeth. She closed her eyes after that. Bag of blood on a pole next to her, a lot of other bags and tubing draped everywhere. Didn’t say another fucking thing, just died the following afternoon while I was at school. I remember thinking she was old, but she was actually only thirty-six.”

“The age you are now.”

“Hadn’t thought of that. Your point?”

“You’ve been through a long war and still took care of yourself.” He turned a page over on his pad. “So, what happened after that? That night.”

“After dark went to Mom’s room, checked under the mattress, then threw everything on the bed: nail polish, eye makeup, underwear, old brassieres with holes in the elastic, wads and wads of pantyhose. Found a partial box of cartridges for a gun we didn’t have anymore, and an old box of condoms in the nightstand. Tried to remember if there’d ever been a man in the house. Imagining her having sex was weird. Couldn’t picture it.” I paused.

“Lots of kids feel that way the first time they think of it.”

“I took the box back to my own room. Considered myself very lucky.”

Zilker laughed.

“Found about thirty dollars in small bills from pockets and change, another four hundred in an envelope taped to the bottom of a dresser drawer.” It occurred to me that I never spent that money.

I puzzled over that until Zilker nudged my foot with his.

“None of the keys in the house fit her vanity—just a cheap metal desk. I went out to the Granada, got the tire iron. There were field fires in the valley that night; I remember smoke drifting through the trees, blood orange moon above the neighbor’s trailer.”

Smoke

, rising silent from the valley floor. It might have been Croatia. I paused, wondering if I’ve mixed up some memory.

“And why do you think the vanity was so important?”

“I don’t know. More money, jewelry. Secrets.”

“Secrets?”

“My whole life, I never felt like she told me the whole story on anything, and then she fucking dies. Like a game show, and now I was going to get to turn over all the pieces on the game board.”

“I want you to hold onto that thought, about wanting the whole story. What was in the desk?”

“Bunch of old letters. Bundle of photographs, mostly Vietnam. Her high school yearbook.”

“Did you read the letters?”

“Might have opened one of them. Kissy stuff. Seemed too nosy.”

“For Christ’s sake. You need to read them. They’re both gone now, it’s permissible. Where are they?”

“Mom’s old suitcase. Put everything in that. Probably still at the Dunhams.”

“You need to get that case. Learn anything from the yearbook?”

“Grizzlies ’70 on the cover. I flipped through it until I found her picture: Donna Palmer. Frosted hair, frosted lipstick. Found Andrew Kent in the senior section. Until then I’d had a notion they met when Dad was at Fort Lewis. Why would she lie?”

“Good question.”

“I remember thinking, I’ll ask her, and realized immediately I wasn’t going to ask her anything again. Never saw it coming. Goddamnit. Was so fucking unfair.”

“The unanswered story.”

“Yeah. I didn’t know if anything she had ever said was actually true. She’d told me my grandparents died when I was an infant. Maybe they just disowned her. Might have been anywhere. Colville, Chewelah, maybe still in Sunnyside.”

“Have you looked? Online services can do that.”

“Don’t have a computer.” It sounded lame.

“Get one.”

“I would have heard from them when I was a kid. Card, money at Christmas. Phone call twice a year. Something.” I stretched out on the sofa, Zilker’s cocktail catching up with me. He sat patiently.

“I put Dad’s photo in the suitcase last, compared that photo to the pile of garbage on the bed. Mom, her whole life so pathetic, dying in a puddle of her own shit and blood, and my father—the fucking sword of God. Kept that picture above my bed through high school.”

I opened my eyes again. Zilker was walking out. I’d fallen asleep and our time was up, my knee stiff from the immobility. I stood, unsteady, and wobbled my way to the nurse’s station, begged a hydrocodone. I swallowed while she watched, then went back to my room to use the toilet. It seemed odd that the bathroom light didn’t come on. A heartbeat later an arm was around my throat, lifting me off the floor.

“Hey, culero. How you feel now?”

Guzman.

“You fat fuck.” I slammed a hammer fist for his balls but hit his thigh, my other hand on his wrist. If he were choking me right I wouldn’t have been able to talk. “You’re just fucking yourself.”

I jumped and arched my back and we both fell. Guzman screamed and let go, then stepped on my calf trying to get away. I half-nelsoned him and was about to break his arm, but he was slippery, blood oozing through his pajamas. Hesitation. Catching his foot, he tumbled forward, chin slamming the edge of the bed hard enough to break his neck. Frank and Tony, two orderlies, ran in. One of them put Guzman down on my bed, getting blood on my blanket.

They could have put him on the floor. “Get him off my bed,” I said. They could wash the floor.

“What’s this shit?” Tony stood in the bathroom, peeling one of the sticky meal tray labels off the motion detector. The lights came on. He turned it on his finger tip. “It’s Guzman’s.” He turned to me. “You’re supposed to tell us before shit like this happens.”

“I want another blanket.” I threw the bloody one out in the hall where a crowd had gathered. They dodged, let it flop on the floor.

Guzman sobbed. Someone brought a wheelchair and rolled him away. Later I learned he’d broken a rib and cut a nice big laceration in his back falling against the crown nut on top of the toilet. Everybody stayed away from me that night. The word on the ward was that I attacked Guzman, and Guzman was locked in his room for his own protection. I wondered if I’d caught anything from his blood, hepatitis or AIDS. It would be so ironic, after all I’d been through—blood spilled, dripped, sprayed on me in a life of war—to end up dying because some junkie bled on me in a hospital. It’s supposed to be safe in a hospital.

Situational awareness; I’d missed it. Maybe the drugs they gave me, like a big piece of cardboard right in front of my eyes. If the enemy was there a second ago he’s probably somewhere closer now. I knew Guzman didn’t like to stay in his room; should have noticed he wasn’t on the ward.

–––

The next morning, I refused the blue pill. Teresa called Zilker and came back a minute later. “He wants you to take half the pill.”

Seemed reasonable. I’d get half of my situational awareness back. Should be enough to keep track of Guzman, the half human.

Zilker arrived at ten and we went into the lounge, but he left the door open. It felt good to be awake, and I sat on the table.

Zilker opened with his usual inquiry about the last day in Afghanistan.

“Why don’t you just get the records?” I had asked him this a dozen times.

“I’ve got them from the DoD, from Landstuhl.” He opened a pack of gum, offered me a stick. I shook my head. “Do you have any friends, Robert? Not in the service?”

“Everyone I’ve known for eighteen years has been Army, sir.”

“Have you looked anybody up?”

“Wouldn’t know where to start.” Half a blue pill started to crawl through me.

He made a face and scribbled on a piece of paper, pushed it across the table. “Website. Together We Served. Start there.”

“Don’t have a computer, sir.”

“They’re a couple hundred bucks. What else do you have to spend your goddamned money on? Get one.” His voice raised and a nurse in the hall glanced our way. He sighed. “Ever go back to the Durhams?”

“Dunhams. I drove up once, they were on vacation, nobody there. Never got around to it again afterward.” I’d been dating Julia at the time, 1992, cousin of one of my platoon when I was in Kuwait City, a pathologically jealous woman. She tore up my address book, opened my mail, and I just ignored it all, too busy all the time trying to catch up on sex I’d missed, telling myself it was love. A second trip to Colville was out of the question.

“You were out for three years. Reserves. How about then?”

“Went to school. Got married. Got divorced.”

He scribbled on his yellow legal pad. “You feel like your time in Iraq had a bearing on the divorce?”

“No.”

“Just no? Any details you want to share?”

“I was in reserves. Reserves weekends pissed her off.” I crossed my arms, leaned back in my chair.

He sized up my posture, marking his pad. “How about high school?”

“Didn’t really stay in touch, sir.”

“You didn’t or they didn’t?”

“I don’t know.” There really hadn’t been time those first twelve weeks, you’d be so tired at lights out, then Saudi Arabia and everything hush-hush. “I got a couple letters from Kaye.”

“The nine-year-old.”

He had this beautiful expectation on his face, and I was going to let him down. “Must have been about twelve by then. Letters always written on notebook paper.”

“And you didn’t answer.”

“I was in Kuwait City.”

“Doing things you didn’t want to tell a kid?”

“Boring stuff, actually. Checkpoint duty, searching stragglers.”

I remembered a beat-up yellow Nissan. Wouldn’t stop. Fifty-cal shot it to pieces. No weapons inside when we dragged out what was left of the

bodies. No IDs either. They always make a big deal of it in movies, but something like it happened a couple times a week.

“I helped look after some torture victims too.”

Zilker raised an eyebrow.

“People the Iraqis tortured. They’d hook electricity to bed springs, pour water all over.”

“I get the picture.”

“Didn’t mean to bother you.”

“You didn’t.” Zilker closed his pad. “We were talking about the girl.”

“I was just doing what I was supposed to do. But how do you tell a kid about that? I think she wanted to picture me doing heroic shit.”

“Anybody else?”

“Her father wrote to me once, right at the end of boot camp. Wisdom, advice.”

“Must have been nice. What’d he say?”

“I don’t remember everything. Seventeen years ago.” It occurred to me that Mr. Dunham made a point of reassuring me he’d keep my trunk safely stored. “One thing. He said that I’d learn from everything that happened to me. Even painful stuff.”

“You think that’s true?”

“I’ve kept my eyes open.”

“What about your own father?”

“Told you about him yesterday. MIA.”

“Doesn’t matter. Find out who he was.”

“I don’t know if I want to, sir.”

Zilker leaned forward; I’d offered him something I didn’t intend.

“It’s just that I think we should let people be remembered the way history saw them. What if I find out he was a drunk too?”

“Then you’ll know more about him than history does. You’re both decorated vets.” Zilker got up and stepped around his chair. “I have a hunch if you learn more about your father, you’ll end up learning more about yourself.” He looked at his watch. “Here’s an assignment. Might get you out of here quicker. Tomorrow I want you to tell me all about that day in”—he stopped and looked at a note—”Kamdesh. Just that one day. Nothing before it, nothing after. Anything you can remember, and then the stuff you’re not sure of.”

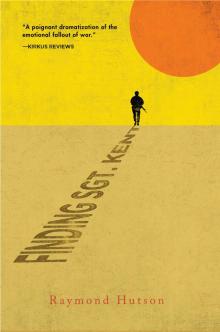

Finding Sgt. Kent

Finding Sgt. Kent